Reality sometimes exceeds anything imagination can conceive of. But when can a fictional composition fixate itself in our imagination as a credible, logical and reasonable description of events that could have taken place in reality? That is a question that writers, playwrights, scriptwriters and poets repeatedly wrestle with, and it seems that no one answer is always correct. The Greek philosopher Aristotle (322 – 384 BCE), whose thought forms the foundation of Western civilization, tried to distill the laws of the natural world and human nature into essential formulas, or molds that would be true regardless of the content poured into them, claimed that it is precisely the quality of fictional imagination which grants a play (or a poem, or a book), its credibility. In other words, if reality exceeds imagination, Aristotle sees things backwards, and determines that fiction- if well wrought- describes and explains reality better than reality itself. The reason for that, as Aristotle saw it, is that reality is filled with “background noise” and exceptional circumstances that get in the way of recognizing and analyzing the essence of reality.

On the other hand, a well written play that is consistently written and does not include background disturbances or other distractions, presents us with a distilled essence of “what is really going on”. It seems that Boris Pasternak, who was born in Moscow, the original Capital of the Russian Empire (and later the Capital of the Soviet Union) in 1890, and died in 1960, managed, in his novel “Doctor Zhivago” to distill and describe the reality of the Russian revolution and civil war in such a whole and coherent manner, so clearly, and so convincingly, that the Soviet Authorities forbade it’s publication and viewed it as a heretical and treasonous manuscript. The Nobel prize Committee, on the other hand, viewed this massive novel as one of the pinnacles of human creativity, a sublime expression of the eternal desire of the spirit of man for freedom, creativity and self-expression- and therefore decided to grant Boris Pasternak the Nobel prize for literature for the year 1958.

In fact, fiction was an inseparable part of Pasternak’s life, who often integrated in his own biography events which didn’t truly occur, but was masterful in describing the causes and background of the development of his worldview. In this he is reminiscent of the renowned German artist Josef Bois, who integrated in his biography dramatic events which eventually turned out to be inaccurate (such as being downed as a German combat pilot in Mongolia, and his rescue by tartar nomads).

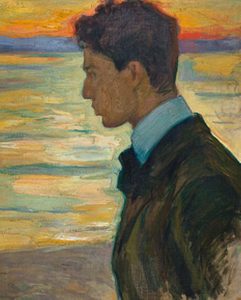

Boris Pasternak was born in 1890 in Moscow. His father, Leonid Pasternak, was a famous painter and his mother, Rosa Kaufman, was a renowned pianist. Young Boris fed, therefore, on the spirit of art and creativity at his mother’s breast. But beyond this, the fact that his parents were renowned and appreciated artists molded his childhood experiences.

In 1891, when he was one year old, on the eve of Passover when Jews celebrate the liberation of their forefathers, led by Moses, from slavery to freedom, from exile in a foreign land to the long journey to their promised land, of all times, the Russian Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovitch, brother of the reigning Tsar Alexander the Third, a decree for the expulsion of all Jews from Moscow to the Western Borderlands of Russia, the “Pale of Settlement” (This was the area seized during the 18th century from the Polish Lithuanian commonwealth, which, unlike Muscovy, welcomed the Jewish exiles from Western Europe in the 12th century. Jews were restricted from leaving this area to the rest of the Russian Empire by the Tsars).

For man of the well-established Jewish community of Moscow, this was an expulsion from the lively high urban culture. Pasternak’s parents, thanks to their renown, were granted an exemption from this expulsion, and were permitted to remain in Moscow, which no doubt greatly affected the development of the young Boris Pasternak. Nonetheless, the shadow of this expulsion, as well as other events in which the Tsarist regime cruelly oppressed its subjects, as reflected in Pasternak’s work in a manner that demonstrated one of Pasternak’s most noteworthy and impressive qualities- beyond his great artistic talent- his courage.

As a boy growing up in Moscow, which was an important cultural center, Boris Pasternak benefited from an excellent education. Alongside standard classes in school, he expressed a great deal of interest in various arts, and in particular in music. While studying the law in the University of Moscow, he made friends of many musicians and composers, and even tried his own hand to composing. From law school he moved on to philosophy, and after completing his studies in Moscow, he travelled to Marburg in Germany, where he studied with the renowned Jewish philosopher, Herman Cohen.

The philosophical views of Cohen shaped Pasternak’s artistic path. It is reflected well in “Doctor Zhivago” and Pasternak’s other compositions and it is it that created the sharp conflict between the manner Pasternak viewed reality and the manner in which the Soviet regime did. According to Cohen, man and all of his qualities is expressed in the human cultural creation. Philosophy can bring man to recognize another man as a human being, as an individual in the whole of humanity, whereas religion enables man to recognize the unique in every individual, and face the divine as an individual, an autonomous unit worthy of recognition, demands, investigation, fulfillment and redemption. It is easy to understand why this individualistic view was scorned by the shapers of the socio-political culture in the Soviet Union, where the word “I” was always viewed as inferior to the word “we”.

Pasternak began his literary career in 1913 when he published- at the age of 23- a collection of poems titled “furrow in the cloud”. At the eve of the outbreak of World War One, he returned from Marburg to Russia, worked as a common laborer in an industrial factory, and after the revolution of October 1917, moved to work in the Education Commissary Library. During that period he also published a number of additional poetry books, and in 1925 he published his first book of short stories “The Childhood of Luvres”.

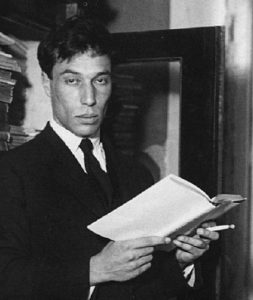

The power of emotions expressed in his poems reminded many of Lermontov. He also translated- an exemplary translation- Shakespeare into Russian. On the other hand the language of his own writing, complex, rich and multilayered, was considered extremely difficult and even untranslatable without harming either the extraordinary aesthetics or the multidimensional emotional and philosophical messages. In his long autobiographical poem “Spekturski”, Pasternak integrated details of his own life in describing the life of an intelligent (supposadely fictional) youth in Moscow. In the Poem “1905” he describes various events in the revolution that took place on that year. The Soviet critics- who were not particularly fond of “Spekturski”, mentioned that in “1905” Pasternak was able to overcome his individualist and anti-socialist tendencies. In the year 1932 Pasternak was rehabilitated by the Soviet authorities, and in the conference of Soviet writers held in 1934, he was recognized as the most important Soviet poem of the time. In 1945 he began to work on the novel Doctor Zhivago which described the complex (and bitter) fate of an intellectual in both Tsarist and Soviet Russia. The work on this massive novel lasted 10 entire years. The Novel lays out the life of a doctor who is also a poet, as a 40 year odyessy, which does not necessarily end with a return home, like Homer’s odyessy, and describes a long journey of a hero of many battles in the Trojan War back to his home island and his wife. After the death of Doctor Zhivago, a book of poetry written by him is discovered, which clarifies how he saw his environment. These poems, which are the final portion of the novel, are considered to be the pinnacle of Pasternak’s accomplishment. This is a nearly impossible and implausible combination of dramatic components with numerous twists in the plot, which includes the 1905 Revolution, the First World War, the Russian Revolution, and the Russian Civil War. But Pasternak, in a way that is reminiscent of how Aristotle saw the connection between fiction and reality, managed to insert an unshakable component of “logic” and credibility into the sweeping and powerful plot.

Pasternak concluded his composition of “Doctor Zhivago” in 1955. At that time, following the death of Stalin and the partial liberalization initiated by Khrushchev, the Soviet regime loosened the supervision and “discipline” it demanded from artists and authors in the Soviet Union, and a number of relatively critical compositions were published in the Soviet Union itself. This state of affairs enabled Pasternak to send the manuscript of the massive novel (710 pages) to an Italian publisher, who signed a contract with him and intended to publish the novel in Italy. In the meantime, the Russian Writers Association (which had by then become a political regime institution to all practical effects) refused to authorize the publication, arguing that the novel described the Russian Revolution as an historic crime and that it’s heroes were “Occupied with their private desire for a more comfortable life, without taking into considerations of the needs and agonies of the masses, which require a certain sacrifice on behalf of all those involved in those historic events, including the gifted intellectuals, who repeatedly trouble the readers with their private mental and physical distress”. The association demanded ‘amendments” to the manuscript, and Pasternak bowed down to this verdict and asked the Italian publisher to return the manuscript to him. The publisher refused, stating that the author was operating under duress. The Russian Writer’s Association did not give up, and sent envoys to Italy to enforce their ruling, but the stubborn Publisher did not give up either and continued to make preparations for publication. Pasternak refused to accept proposals to write about other subjects which would reveal life in the Soviet Union in “All of their glory”. This refusal, which required a great deal of courage, and the publication of the “forbidden” book, derived, in the opinion of many reviewers, from Pasternak’s opinion that the perception of reality described in his book was essential to the public just as it was essential to the author. It was also important to clarify and display to the readers, whoever they might be, that even after a long chain of difficulties, disasters, wars, tragedies, oppression, silencing and fear, there was still value and still a role for the human spirit that sanctifies the truth, love and the hope for a better world

.

As these words are being written, in the year 2017, a century after the Russian Revolution, it many be worth recollecting another Jewish Poet, Shaul Tchernichovsky, born 15 years before Pasternak, and who passed away, more or less at the same time as Pasternak began to work on Doctor Zhivago. In his book, “I believe”, Shaul Tchernichovsky speaks out to the human spirit, wherever it many be, and expresses his unqualified faith in it, na din the value of the dream:

Rejoice, rejoice now in the dreams

I the dreamer am he who speaks

Rejoice, for I’ll have faith in mankind

For in mankind I believe.

Pasternak, who located the hero of his novel on the continuum of time during what might be called “Interesting times” in the Chinese sense, wove his plot in a manner which does not distinguish between general history, the wars, the famine and so forth, to the personal and even spiritual history of the protagonist. In this integration of social history to that of the individual, he might be considered a heir to the path set down by the great Russian Novelist Lev Tolstoy (“War and Peace”).

Neither Pasternak nor Tolstoy dwell overmuch on the question of who exactly held power in state or society. Both of them emphasize that only he who is capable of listening to the voice of conscience can rule the soul. “I am only here to try and understand the terrible magnificence of the world and to know the name of things: if my strength is insufficient, my children shall complete this testimony”. Those were the words placed by Pasternak in the mouth of the young Lara at the beginning of the novel Doctor Zhivago.

A clear cause of contention between Pasternak and the Commissars who censored his book was the preferential treatment he accorded the individual over society. “In this new way of existence, dictated by the heart, and in this new way of relations called the kingdom of God, there are no nations, only individuals”, write the commissars. “In the harsh years of the Civil War it becomes clear that as far as the author is concerned there are no human beings, there is only he himself: an individual whose interests and agonies are the only thing that matters. An individual who does not even feel he is part of a people. In our opinion Doctor Zhivago displays in his personality a clear type of the past Russian intellectual, a man who loves to talk about the suffering of the people, but who can do nothing to assist the masses. This is the type of ‘intelligent’ citizen, who will not interfere in occurrences so long as they do not impact on him directly, but should an inconvenience be inflicted upon him, however minor it might be, he would be prepared and capable of inflicting a great wrong on the masses, merely to restore his own comfort. There may have been, and might yet exist such people amongst us, but we must ask whether they deserve to be the centerpiece of a novel such as the one which you have written with your great talent”. In a conversation with a British journalist, years after he received that same letter from the association of Russian Writers, Pasternak answered them in his own way: “I had to write about the forces which instill beauty in life, love, victory, success, I had to display the many hues and colors of this world. I am a man of color and through color I saw all good things, and I believe that the colors I used in Doctor Zhivago are true. I, in a very clear way, am an exceptional member of a society which has chosen to disregard the individual and focuses only on the masses. I furthermore believe that the masses cannot exist save as a collection of individual, even exceptional, people”.

“This book changed my life and my destiny”, he went on to tell the British journalist. “This did not occur in a fit of absent mindedness. I knew what would happen in advance, my heart told me that my life and destiny would change. It is the job of the artist to display reality. I told myself that I must write what I saw, what I witnessed, as an historical truth. I told myself that I must do so while loving variety, the hues, the colors, the times, and the people. To provide the philosophy of life, of love”. Perhaps the full tragedy of Pasternak is expressed in his subsequent simple phrases: “Now I desire to write a new story, not a prosaic account of our country, but a description of life itself. But perhaps I cannot do so. I am a Soviet Citizen and live in the Soviet Union, and I think that the state will not cease troubling me, but I still want to write about love, about life in the Soviet Union”. That novel, of course, was never written.

Pasternak died in the year 1960, just as the hero of his novel dead, from a heart attack, but in his case this occurred in solitude, and as a complication of pneumonia. Word of his death was published in a few lines in the Writer’s Association paper, and yet over ten thousand people came to his funeral. The Soviet Government, the Communist Party and the Writer’s association did not send representatives. The renowned Pianist Sviatoslav Teofilovich Richter played melodies of Chopin that were beloved by Pasternak. The writer Korney Ivanovich Chukovsky delivered a eulogy in which he said that “Pasternak was a glorious warrior who showed us all how a writer must be ready to defend his ideas, without fear and without consideration of the opinions of his own contemporaries, so long as he is convinced that his words are truth and that the principles he is fighting for- are holy”.

Boris Pasternak left a widow, Zinaida, and two sons, Yevgeny, an architect, and Leonid, a writer. His two sisters, who lived in London at the time were denied entry to the Soviet Union. In a poem found after his death (Again, much like his protagonist Doctor Zhivago), he wrote: I died as a trapped animal… somewhere, there is freedom and light… behind me rises the din of the chase and there is nowhere to run to… whatever may be, I stand at the edge of my grave and believe that in due time good will triumph over evil”.

Five years after his death, in 1965, the Hollywood film “Doctor Zhivago”, based on his novel, reached the screens, directed by David Lane. The movie remains one of the ten most profitable movie films of all times.